What is Urban Forestry?

By: Ruth Williams (email)

A major difference between the urban forest and the tradition forest becomes obvious if you list benefits of each. The urban forest does not make much money from selling wood. In most cases, urban trees are appreciated for other reasons than furniture, paper, and firewood. Even if you do not live in the city, you probably cannot imagine the thought of cutting down the tree shading your back porch for paper.

So, what makes an urban tree valuable?

- Habitat for wildlife: squirrels, birds, raccoons, etc.

- Reduction in storm water runoff (root and soil absorption)

- Increase in property values

- Air pollution like smog becomes trapped in leaves

- Slow global warming by using carbon dioxide in photosynthesis

- Shade makes buildings cooler in the summer

- Pleasing views, smells, sounds, etc.

…. Just to name a few!

Have you ever noticed that trees planted in parking lots don't usually get as big as a forest tree might? Trees need water and nutrients from the soil to grow, and the soil surrounding buildings and construction does not supply as many resources as forest soil.

Far Reaching Roots

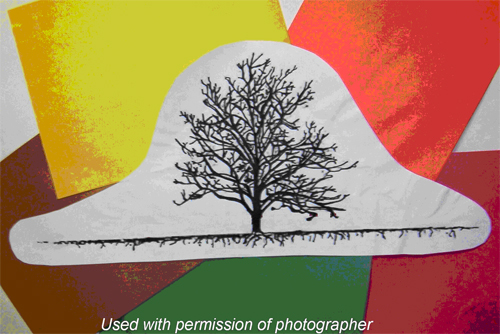

Many people imagine that a tree's root system looks similar to the branches of the top half of the tree. Think far reaching instead of deep (figure 1). Actually, the roots that collect water and nutrients are within one foot of the soil surface. They can travel out as far as two to three times the height of the tree!

Remember our parking lot tree? In most cases, its roots can't travel very far before reaching pavement. Trees planted close to buildings have the same problem. If the roots have less soil to explore, the tree can't find as much water and nutrients. Periods with little rain cause big problems for these trees.

Figure 1. The tree's feeder roots are far reaching rather than deep.

Soil Compaction

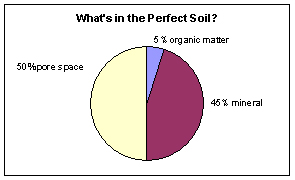

What makes up the perfect soil? About 50% is space (figure 2). Lots of traffic and construction can result in soil compaction, reducing the amount of space in the soil. Soil compaction can be measured with a penetrometer (figure 3). If a great amount of force is required to push the penetrometer into the ground, the soil is compacted.

Compaction can limit the amount of soil available to the roots, just like pavement. Water, nutrients and air travel in the pore spaces. If the soil does not have much pore space, water tends to puddle on the soil surface. Have you ever noticed a tree surrounded by puddles of water? Try to push a stick into the ground near that tree. It might break before you can push it in.

Compaction also shrinks the size of soil pores. Have you ever tried to use a coffee stirrer as a straw? It requires more “sucking-power” than you may have to pull your coffee through such a tight space. Tree roots experience the same problem when soil pores become compacted.

Figure 2. Ideally, soil contains a network of large pore spaces for water and air.

Figure 3. A penetrometer measures the force used to penetrate soil. The soil is compact

if it requires lots of force to push the penetrometer into the top foot of soil.

The Nutrient ‘Tug-of-war'

The pH scale compares solutions in terms of alkalinity and acidity. A pH of 7 is neutral. A pH of 1 is extremely acidic. A pH of 14 is extremely alkaline. Drano is a very alkaline solution. Your stomach contains a very acidic solution.

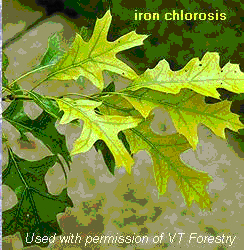

You can measure the soil's pH by making a solution of about half soil and half distilled water. Most soils have a pH between 3 and 8.5. Most trees prefer a soil pH below 7. If the pH is too low, root tissue may be burned, but if the soil pH is too high nutrients needed for growth are “held” by the soil. For example, the soil could have plenty of Iron, but if the pH is 8.5, the soil will chemically “hold” the Iron so tightly that the tree's roots cannot chemically “pull” it away. Have you ever noticed a tree with yellow leaves in the middle of summer? Too little Iron is one of many things that can cause chlorotic leaves (figure 4).

Concrete from construction activities, foundations, and sidewalks can raise the pH of nearby soils.

Figure 4. Iron deficiency can result in yellow leaves during summer.

Mulch: A quick, cheap fix

Mulch is one inexpensive way to improve the quality of soil. A layer of mulch can mimic the layer of leaves on the forest floor. Fewer weeds and grass grow through the mulch layer to compete with the tree. Moisture remains in the soil longer. Soil temperature remains warm long into the winter, so roots can continue to absorb water and nutrients. As mulch decomposes, organic matter is released into the soil, reducing soil compaction.

Remember to keep the structure of a tree's roots in mind when you spread the mulch. Do not pile the mulch in a mound near the trunk. Instead, protect the far-reaching roots and give the tree's trunk plenty of light and air.

Questions:

- What is one reason that you should spread mulch far instead of piling it against the tree trunk?

- What instrument measures soil compaction?

- Why might soil pH be higher near a sidewalk than in a wooded area?

Answers:

- Mulch piled against the tree trunk can cause decay and insect problems, because moisture is held against the trunk and air does not circulate. Mulch that is spread far out to the tree's dripline or beyond protects more of the root system.

- A penetrometer measures soil compaction.

- The concrete from the sidewalk and other construction can leach into the soil, raising the pH. Decomposing leaves and other organic matter in a wooded area causes the soil pH to be lower than many urban areas.